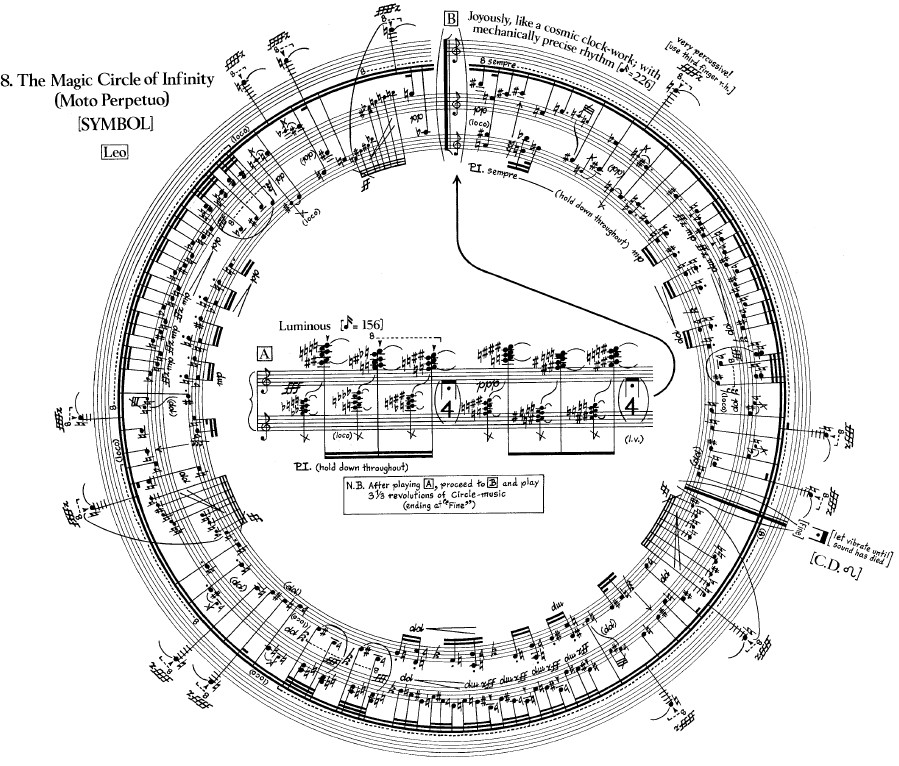

The composer gives these zodiacal vignettes evocative titles (“Primeval Sounds,” “Night-Spell I,” “Spring-Fire,” and so on) and opens up coloristic possibilities by “preparing” the inside of the instrument with various foreign objects.Īlong with producing spectral glissandos, eerie harmonics, Aeolian-harp strums and Messiaen-like twitters on the keyboard and inside the instrument, the pianist also is required to utter a wide range of vocal effects and talismanic chants, all to intensify the expressive effect. Hearing the dozen amazing pieces for amplified piano that make up Makrokosmos I, as performed by Marie Alatalo reminded one of Crumb’s genius in fashioning timbres to make other timbres. No composer has expanded the available color-palette of the modern piano as brilliantly as Crumb has in his Makrokosmos, the first two books of which comprise 24 “fantasy-pieces” based on signs of the zodiac, drawing on the myths and symbols of ancient civilizations, his love of Debussyan impressionism and his own acute poetic imagination to conjure sound-worlds at once cosmic and ritualistic, still and teeming with life. The triumphant results augured well for the remaining events of this important retrospective honoring a true American original. The first concert, primarily devoted to three of the four books of Crumb’s style-defining collective masterpiece, Makrokosmos (1972-79), took place on Friday night. The event was conceived by Queen-director of performance activities at the institute-and is made possible by a grant from the American Music Project.

Martin and Queen, along with their faculty colleagues of the Music Institute of Chicago and guest artists, are celebrating the man and his music with a George Crumb Festival of two concerts, a panel discussion and a score display this weekend at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston. Dedicated performer-champions of Crumb’s music, such as soprano Barbara Ann Martin and pianist Fiona Queen, are helping to keep the flame alive.

The composer turned 90 in October, and the renewed attention his music is receiving by virtue of that anniversary marks Crumb as a durable survivor of the American avant-garde, perhaps because he was never a part of it. And last April the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center gave the world premiere of the composer’s KRONOS-KRYPTOS for five percussionists. Recordings continued to appear on Bridge as part of that enterprising label’s ambitious project to commit to disc virtually every note he has written. A new-music community swept up in post-minimalism, neo-romanticism or trendier hard-edged strains of rock- and jazz-influenced art music, appeared to turn its back on his delicate, exquisitely crafted music.īut his voice would not be stilled, and Crumb bounced back in 2002 with Unto the Hills, the first of his many songbooks based on folk Americana, and the start of what became a kind of creative Indian summer. Throughout much of the ‘90s, his pen fell silent. Yet by the 1990s Crumb’s output grew slimmer and his creative life looked as if it would not survive his fame. Few of his colleagues were more successful at reaching out to an audience of younger listeners and musicians alike. Using a language of extended instrumental and vocal techniques, conventional instruments outfitted to produce unusual sounds, and elements of non-Western musical practice, Crumb created highly evocative and poetic dreamscapes of mystical, exotic, otherworldly resonance.Ī string of masterpieces, such as the quartet Black Angels (in which the string players shout and play water glasses), his Pulitzer-Prize-winning orchestral work Echoes of Time and the River, and Ancient Voices of Children (the first of many Crumb settings of poetry by Federico Garcia Lorca) established him as one of the most fiercely original voices in new American composition. The modest, soft-spoken composer from West Virginia startled everyone by crafting a unique sound world the likes of which had never been heard before.

The Music Institute of Chicago presented the first concert of its George Crumb Festival Friday night at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston.ĭuring the 1970s, George Crumb hit the contemporary music scene like a clap of ear-opening thunder.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)